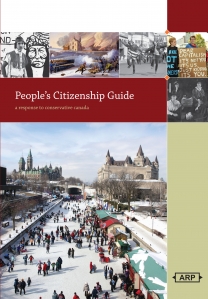

Tonight, at McNally Robinson [please click for event information] in Winnipeg, The People’s Citizenship Guide: A Response to Conservative Canada will be launched. This short 80-page book is a direct response to Citizenship and Immigration Canada’s Discover Canada: The Rights and Responsibilities of Citizenship, which has been widely critiqued for its restrictive and overly-politicized definition of Canadian identity (for examples or critiques see the Globe and Mail, Andrew Smith’s blog, my summary of initial reactions on AH.ca, Ian McKay’s podcast on the right-wing reconception of Canada). As in the official immigration guide, The People’s Citizenship Guide’s editors, historians Esyllt Jones and Adele Perry, have brought together a diverse group of scholars in order to succinctly reflect on the nature of Canadian citizenship and modern-day Canada.

The People’s Citizenship Guide closely mirrors Discover Canada. It is broken down into the same ten sections as the book published by the government. Both texts address citizenship and identity, history, governance, symbols, economy, regions and issues Canadian citizens should consider

The biggest difference between these two works is that Canada’s colonial and liberal legacy is directly acknowledged in The People’s Citizenship Guide. Rather than taking Canada as a historical inevitability, with only ‘regrettable’ instances of social and ethnic conflict, The People’s Citizenship Guide more explicitly emphasizes that “Canada is a construct, a product of collective imagination and history” that in the past (and today) has included some people, while excluding others.

Treatment of Aboriginal peoples serves as a good example of the difference between the two guides. When the Discover Canada Guide was first released, historian Christopher Moore lamented the lack of discussion about Aboriginal people and treaties in the government’s portrayal of Canada’s past. The emphasis of the government’s text is on cooperation rather than conflict and dispossessions, making it seem that First Nations unconditionally welcomed European newcomers. The People’s Citizenship Guide is much more explicit about the inherent nature of First Nation’s sovereignty and the legacy (and complexity) of treaties and land dispossession.

At $14.95, it is unfortunate that The People’s Citizenship Guide will not be as accessible as the free Discover Canada Guide (available as a PDF online). In many ways, Jones’s and Perry’s text will better serve immigrants to Canada. Particularly in their discussion of the provinces and territories, The People’s Citizenship Guide is much more frank about each province’s and territory’s economic prospects, political challenges and complicated histories. For many immigrants it could be a helpful tool in assessing where in Canada they would like to settle. More generally, The People’s Citizenship Guide represents a more diverse and complex picture of Canada. The book pays greater attention to the rights of Canadian citizens and the resources available when those rights are infringed upon (though, both guides could discuss the Supreme Court of Canada in greater detail).

This book is a welcome political intervention. From its title through to its back cover, The People’s Citizenship Guide’s politics are open and easily discerned. Such overt and provocative language, which on the first page labels the vision of Canada presented in Discover Canada as “nationalistic, militaristic and racist,” may turn people off the book before they can digest its important content. That being said, the explicit nature of the book’s politics provides excellent contrast to the political perspectives that are often left implicit in Discover Canada. In publishing The People’s Citizenship Guide, Jones and Perry should be lauded for calling explicit attention to the politics of citizenship.

Indeed, one of the book’s strengths is that it closely follows the structure of Discover Canada. Both guides can literally be read side-by-side. There is significant pedagogical and civic merit to this exercise. Reading both books’ sections on trade and economic growth, for example, illustrates the political differences between these texts. Discover Canada begins its section on trade and economic growth with these two sentences:

“Postwar Canada enjoyed record prosperity and material progress. The world’s restrictive trading policies in the Depression era were opened up by such treaties as the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), now the World Trade Organization (WTO)” (DC 24).

The People’s Citizenship Guide takes a broader and more global perspective on the postwar period. Its section on trade and economic growth begins this way:

“The Canadian economy forms part of an unequal global economic system, a system which, shaped by the legacies of colonialism, continues to privilege industrialized nations over those of the global south. The postwar period was a time of economic boom for wealthy nations like Canada, and many Canadians achieved greater material comfort than they had previously enjoyed” (PCG 31).

This type of comparison makes the Discover Canada Guide and The People’s Citizenship Guide useful for teaching critical reading skills in high schools and introductory university courses.

The People’s Citizenship Guide does not intend to be a replacement for Discover Canada. To find out about government structures, how to vote, or the date of important national observances – like Sir Wilfrid Laurier Day (Nov. 20 for those of you who regularly fail the Historica-Dominion Institute’s quizzes) – one is better to consult the government’s official guide. If, however, you would like a short introduction to Canada that represents the diversity of Canadian experiences and contextualizes many of the critical issues currently facing Canadians, The People’s Citizenship Guide provides a useful starting point.

The People’s Citizenship Guide is being launched tonight in Winnipeg at 7 p.m. in the atrium of McNally Robinson at Grant Park. You can purchase a copy of the guide from Arbeiter Ring Publishing.

Source: http://activehistory.ca/2012/02/the-peoples-citizenship-guide/

Great Post.

ReplyDeleteOnline Learning

Skills Assessment